The Year We Won It All: A Behind-the-Scenes Oral History of the 76ers’ Epic 1983 Championship

Forty years ago, after a series of heartbreaking near-misses, the 1982-’83 team landed Moses Malone and didn’t look back. This is the behind-the-scenes story of one of the most dominant seasons in NBA history.

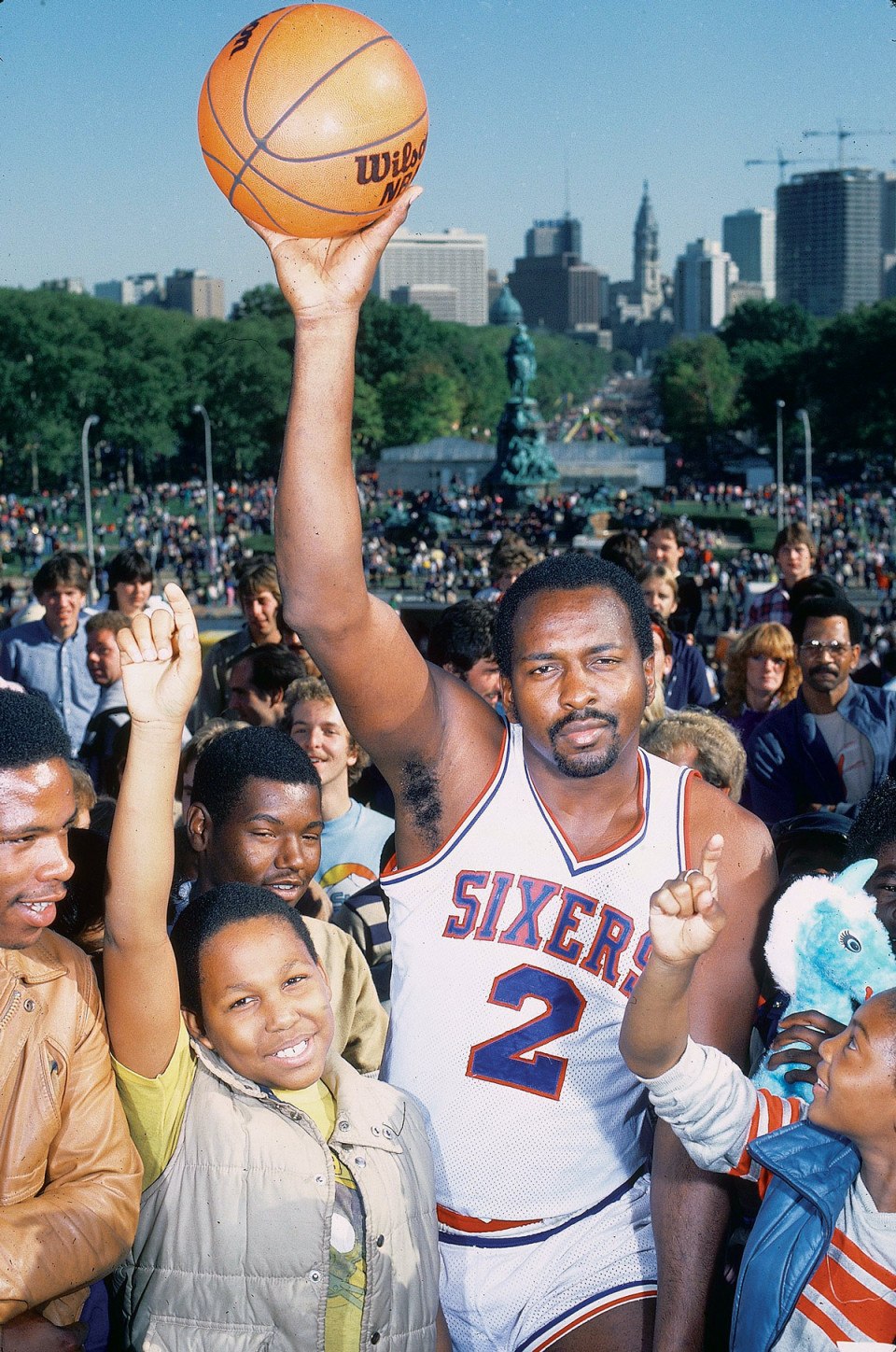

On the eve of the Sixers’ 1982-’83 season, Moses Malone poses with fans on the steps of the Philadelphia Museum of Art. The 76ers would go on to win the 1983 championship. / Photograph by Manny Millan/Sports Illustrated/Getty Images

Philadelphia’s status as a tortured sports city isn’t a permanent designation. Zoom past the days of Connie Mack. Brake before the Philly Special. Turn off the notifications. Turn down the volume on WIP. The city has known the bliss of an ass-kicking team. Forty years ago this month, the 76ers crushed the opposition en route to a 65-17 record and the NBA championship.

There were no struggles, no controversies, no heartache. It was beautiful.

You can tell from the photo — an impromptu snap:

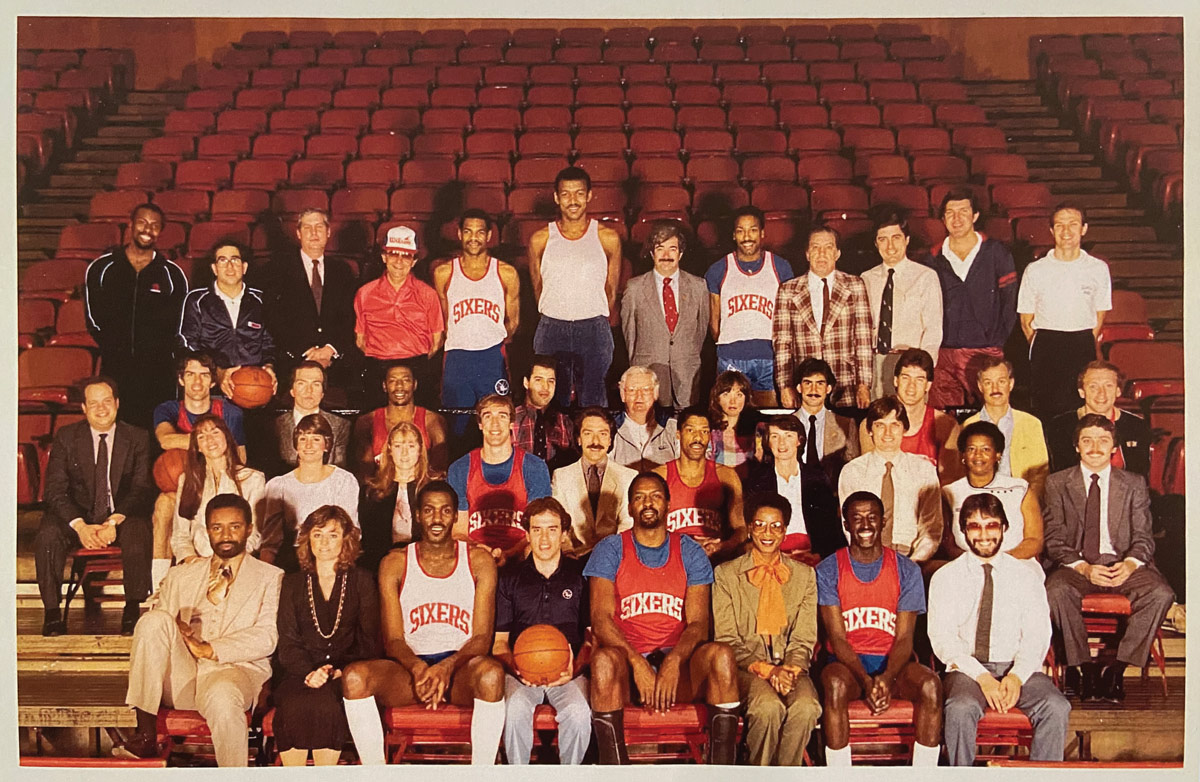

An impromptu photo of 76ers players and staff taken during the 1982-’83 season / Photograph courtesy of Tim Malloy

These Sixers were rolling. Steve McKenna, the team’s assistant ticket manager, says he suggested everyone at the Spectrum commemorate the moment. Players and coaches and administrative assistants all together — look at the smiles. They know they’re involved in something special. They’re young and confident. This is their time.

Six years — three whiffs at the NBA championship. The favored Sixers blew a 2-0 lead to the Portland Trail Blazers in 1977. Three years later, a smiley rookie point guard named Magic Johnson jumped center and closed out the Sixers at the Spectrum. The next year, the team took a 3-1 lead into Game 5 against the Boston Celtics in the Eastern Conference finals — and lost three in a row. That the Sixers succumbed to the Lakers in 1982 without calamity felt quaint.

The 1982-’83 season brought indefatigable MVP center Moses Malone, deemed the perfect complement to Julius Erving, the beloved scoring artiste and Philly institution. There was also a dynamic backcourt, a banger who emerged from the Italian league, a devoutly Christian super-sub, and a seasoned head coach. It all led to “beautiful basketball,” recalls Hall of Fame Milwaukee Bucks guard Sidney Moncrief. “That was just the way that game was meant to be played.”

Here’s how it all happened.

Part I: “I can probably get Moses Malone.”

Harold Katz, 76ers owner: I met the previous owner, Fitz Dixon, only at the closing of the deal [in 1981], and he said I should I fire everyone. I don’t know if he was serious or not serious.

John Nash, 76ers assistant general manager: Harold Katz wanted to be involved and was involved. There was pressure from that standpoint: new owner asking hard questions, interacting with coaches and players and front-office personnel. He put pressure on Pat Williams.

Pat Williams, 76ers general manager: Harold was a basketball fanatic. He followed the game closely. He had strong feelings from the get-go, and we knew this was going to be a different adventure.

Katz: I didn’t buy the team to make money. I bought it to win.

Williams: He had a dish in his backyard. He could pick up college games late into the night. Harold was a night person. Then he’d call the next day: “What do you think of this kid at New Mexico State?” “Harold, I was asleep.”

Dorothy Summers Gabriel, administrative assistant, 76ers executive office: If Harold would call and Pat would be in an intense conversation, or if Pat went to Harold’s house for a meeting, we were always nervous that something was going to happen, like he was going to fire him on the spot.

Steve Mix, 76ers forward, 1973-’82: I do remember a locker room that was kind of solemn [in 1982]. Everybody knew that was our chance and there were going to be changes made the following year.

Jack Swope, 76ers director of promotions: There was a lot of frustration, because you felt like you should be there. And the fans were frustrated.

Summers Gabriel: “We owe you one” was, oh my God, the worst ad campaign ever.

Swope: You wanted that moniker off your back.

Ron Dick, 76ers group-sales intern: You don’t tell Philadelphia people you owe them anything. They’ll never forget that. I remember my cousin saying, “In ’77, you owed us one. How many do you owe me now, man? How many?” You’re my cousin. Your mother and my mother are sisters. Like, could you lighten up a little?

Victor Sonder, co-creator of the “We Owe You One” ad campaign: For an advertising campaign to last 50 years, it can’t just be bad. It has to have some real strike force with the public.

Nash: I think everybody enjoyed the success of the team — how good they were and how competitive they were. But they also recognized that the Celtics and the Lakers were formidable. If ever they could get a center that could compete with [Robert] Parish or Kareem [Abdul-Jabbar], that would be the missing piece of the puzzle.

Katz: I was taking my family to Lake Tahoe. I just started jotting down numbers. I said, “If I did this, if I did that, I can probably match and get Moses Malone.”

From left: Howard Eskin, Moses Malone, Harold Katz and Billy Cunningham on the set of The Howard Eskin Show in October 1982. / Photograph by Manny Millan/Sports Illustrated/Getty Images

Malone, then 27 and with the Houston Rockets, was arguably basketball’s best center, though he stood maybe six-foot-nine and had hands so small that “he couldn’t palm a basketball,” says Steve Patterson, whose father, Ray, was the general manager during Malone’s time in Houston. Those shortcomings mattered little. What did? Malone’s contract with the Rockets was up — and Katz was convinced the Rockets couldn’t match his offer.

Alex English, forward, Denver Nuggets: You were getting a machine — a rebounding, scoring machine.

Steve Patterson, general manager, Houston Rockets and Portland Trailblazers: One of the best rebounders I’ve seen, maybe the best. He couldn’t really catch the ball. He’d tip it up and tip it up until he could get it away from the guy on his back so he could grab it with two hands. He had an uncanny ability to figure out where the ball was going to be when it came off the rim and go be there to get that rebound. It was just shocking to watch.

Robert Parish, center, Boston Celtics: You can’t say he’s a jump shooter, hook-shot artist. Moses was all about positioning. He got the best position of anybody I played against — deep post-up, ideal position for a rebound. He had those instincts that every shot was going to be missed. He had a very high motor. He was nonstop. He never seemed to wear down.

Ron Rabena, 76ers assistant equipment manager: Moses would come off the court, he would sweat like a pig. He’d drink, like, five, 10 waters. In a huddle, we’d have the little tray — he would empty the tray himself.

Katz: We land at Lake Tahoe, I called [Malone’s agent] Lee Fentress, and we all met in New York. I told the wife, “I’m planning on leaving tomorrow.” She wasn’t thrilled, but she bought in to the idea I think this will win it all. I came back a couple of days later.

Nash: Moses was leaving from New York [the next morning] on a Nike trip, which is maybe why we selected New York.

Part II: “No ‘ferred.”

Williams, a master wheeler-dealer, wasn’t at the negotiation. He was in China with Julius Erving. The Sixers’ contingent featured Nash, Katz, and head coach Billy Cunningham, whom Nash summoned from a golf trip in North Carolina.

Nash: Billy was concerned that Moses was willing to come in on a championship-caliber team and accept a role that would not necessarily make him as dominant an offensive player as he had been in Houston. The plan was for Billy to visit with Moses, clear the air, and give us a thumbs-up or thumbs-down.

Seven o’clock came and went, and no Billy Cunningham. Seven-thirty, no Billy Cunningham. At about 10 minutes of eight, rap, rap on the door. Here comes Billy, carrying his golf clubs into the room: “Do you know how much they want for a cab ride at Newark Airport? I took a bus to the bus terminal.”

Billy Cunningham, 76ers head coach: The cab was $70 to get to the Hyatt on 42nd Street, next to Grand Central Station. I sit down, and all of a sudden, it’s, “Will you take $2 million a year?” And I’m going, I just took a friggin’ bus [laughs] — and it wasn’t even my money — because I thought the price was ridiculous.

I sat down with him, the two of us. I said, “This is what we’ll expect from you joining this team.” To be a dominant force rebounding, and we needed him to get the ball out so we could run. We were a very athletic, quick team. If we didn’t have anything at the other end, we’d be looking to get him the ball inside. It was basic. It wasn’t brain surgery. He understood that completely, and he performed it beautifully.

Katz: Frankly, the money made the actual difference.

Nash: We negotiated until about 2 a.m. Everything we agreed to was written out longhand.

Katz: Moses starts reading, and he says to [his lawyers], “No ’ferred. I’m not having no ’ferred.” He meant deferred income.

Patterson: He was a lot smarter than people gave him credit for.

Nash: The [hotel’s] business office did not open until 6 a.m. Larry Shaiman [Katz’s attorney] and I, we made copies of everything that had been written. We wanted to get the document to Houston as soon as possible. Shaiman and I jumped into a car, drove back to the offices in Philly. There was a 15-day period where the team could determine if they were going to match or not match. We wanted the 15 days to start immediately. I called Ray Patterson, who was the general manager of the Houston Rockets, and told him we were sending one of the secretaries, I believe it was Marlene Barnes or Evelyn Canada, to hand-deliver the document. This was motivated by Harold Katz. Harold was never one to let grass grow under his feet. [Canada says she didn’t deliver the contract. Barnes died in 2016.]

Patterson: They wanted him to stay. The issue was purely Charlie Thomas had just bought the club, and Charlie literally said, “Christ, Ray, I paid $12 million for the whole goddamn team and now you want me to pay that for one player.” [laughs]

Williams: It was a $13 million deal, which today would pay the ball boy. But back then, that was just staggering.

Katz: Nobody in team sports made $2 million [a year].

Moses Malone with Big Shot at a Love Park rally / Photograph by Manny Millan/Sports Illustrated/Getty Images

Tim Malloy, assistant group sales director: We flew him in for a secret medical examination. I met him at the curb in a 1977 Toyota Corolla hatchback. We drove from the Philly airport to Veterans Stadium, which is where our offices were. The Phillies were playing the Reds or the Cardinals. I had to drive real slow once I got into the Vet. The people were all walking around me, going into the game. Somebody looks into the window. Picture the stadium parking lot — it’s crowded.

“Hey, check that car, that looks like Moses Malone is in that car.” I keep driving really slow.

“That is fucking Moses! Yeah, he’s in there! Hey, hey!” I just keep moving.

That guy shouts to the next guy, “That’s Moses!” Now they start banging on my car, like I’m in a war zone.

Moses is loving it: “I can walk down the streets in Houston and nobody bothers me.”

Part III: “They had almost an all-star team as a starting lineup.”

Eventually, the Sixers sent Caldwell Jones and a first-round draft pick to Houston in a sign-and-trade deal. Malone, who was close friends with Jones, balked. Katz knew what to say, Williams recalls: If Malone didn’t approve the deal, NBA commissioner Larry O’Brien could demand the Sixers offer Houston a better player — even, potentially, Julius Erving — as compensation.

Malone understood what had to be done. The Sixers had their man and still had The Man.

Paul Gilbert, director of production, NBA Entertainment: I started watching Julius when he was in the ABA. His game was so exotic. Nobody had played like that before. You could watch on any given night and say, “He’s going to do something I haven’t seen before or do something where I’m going to jump out of my seat.”

Marques Johnson, forward, Milwaukee Bucks: Doc knew that once he got anywhere near the three-point line, he’s able to take two steps and dunk. His ability to take off from distance and hit the dunk was such a demoralizing shot in those days. When Doc did it, it just broke your spirit.

Cunningham: He accepted the role of ambassador and was just phenomenal. People tend to forget and feel that basketball started with Bird and Magic.

Terry Lyons, NBA public relations, 1980-2008: Doc was the best at giving very well-thought-out answers to questions that were tough. It started to have a major effect on the way players thought it had to be.

Earl Cureton, 76ers forward: The thing that stood out to me was the way he carried himself, and the way he dressed. I work for the Pistons right now. I go to 41 games a year. I wear a suit every single night. They say, “Why do you have a suit on every single night?” I say, “Because Dr. J wore a suit all the time.”

Lyons: He would sign autographs everywhere. They played Milwaukee in the playoffs. We went across the street to a bar. I looked out the window, and Doc was walking back to the Hyatt. On the median of the road, he was signing autographs. [laughs] Traffic going by him on both sides, and those kids tracked him down. You couldn’t believe your eyes.

The team stretching during its October 1982 training camp at Franklin & Marshall College / Photograph by Manny Millan/Sports Illustrated/Getty Images

Dan Issel, center, Denver Nuggets: They had almost an all-star team as a starting lineup.

Rabena: Bobby Jones didn’t say two words. Maurice Cheeks didn’t say two words. But when you put ’em on the court … I mean, these guys were dominant players.

English: [Jones] was long, lanky, and he was relentless. He knew himself and knew what his game was. His game was being the defensive stopper on that squad.

Sidney Moncrief, guard, Milwaukee Bucks: Andrew Toney was un-guardable. If you look at all the components of an offensive player, he could do everything. And you couldn’t really push him one way. I studied him, and it’s nothing you could do that could stop him from scoring, beyond double-teaming him and getting the ball out of his hands, which we probably should have done more. [laughs] A lot of teams should have done that more. He was very smart. Very, very smart. Whatever you did, he had a counter. I always put him right there with Michael [Jordan].

Johnson: It was way too much talent on one team to be fair.

Cureton: I called Andrew Toney, and I said, “Man, we’re winning it all this year.”

Moses Malone and Julius Erving on the November 1st cover of The Sporting News / Photograph via Sporting News/Getty Images

Part IV: “Teams felt us coming”

Moses Malone was the dominant center the Sixers had lacked since Wilt Chamberlain left the team in 1968, but his character may have exceeded his basketball abilities.

Franklin Edwards, 76ers guard: We had lost a game, and he and I went to dinner. He said, “Man, when we lose, I can’t sleep at night.” That showed me his commitment to winning with that team, and it really changed my commitment.

Mark Whicker, sports columnist, Philadelphia Daily News: He was not hard to adjust to, because he gave them a little bit of an edge. They had a bunch of really nice guys who played well, but they were not a real brash bunch of guys. Their confidence came and went at times when they played the best teams. Moses had tremendous confidence.

Williams: There was just a whole different atmosphere in the gym from the first day. These guys have a different focus. This is not about having a good season; this is about winning it all.

Parish: Their attitude changed. I felt like they believed they could win it.

Neil Funk, 76ers announcer: Moses just figured out: This is what this team needs, and this is what I can give them. I can rebound. I’ll get us second shots. I’ll score when I have an opportunity. The type of player he was lent itself to fitting right in.

Cunningham: His hero was Julius Erving. All he wanted to do coming to Philadelphia was to help Julius win a championship. It was a sigh of relief that we weren’t going to have competition between two great players. It was, “How do we help each other?”

*Julius Erving, 76ers starting small forward: I’m second in command on that team. I’m the captain, but Moses is really driving the ship.

Issel: He realized he was playing with a lot of great players, and I think he kind of tempered his game somewhat from being an incredible individual to being a team player more.

Moncrief: People see the spectacular plays, but what they don’t see is some of the grunt work he put in offensively and how he transformed his offensive game. Julius became a lot better defender. Early, he was like a lot of players who went through the motions, because he was long and good. He could work on the defensive end. That became important to him. But the slow bringing the ball down the court, backing guys off, fighting to get post position — that’s grunt work. Those are the types of things that make players great.

Funk: They were really unselfish, and that started with Cheeks. Maurice didn’t care if you hadn’t had a shot in 10 minutes. If you ran the offense, made the cuts you were supposed to make, Maurice would get you the ball. There was very little standing around while one guy went to work.

Maurice Cheeks shoots over Michael Cooper at the Spectrum / Photograph via Focus on Sport/Getty Images

Williams: Billy was at the peak of his game.

Funk: Billy never made it personal with the players; it was all about performing as a member of a team. I just think Billy was way overlooked as a coach. He had a way about him of not just handling players but managing a game. He had a great understanding of who he could get on and who he needed to back off a little bit to give them a little more leeway. He did an unbelievable job. That was a team that could get away from a coach.

Russ Schoene, 76ers forward: He was a players’ coach totally, and he just had confidence in the guys. He let the players more or less determine the game.

Rabena: I will tell you, unequivocally, not once did I hear a voice raised that year with this team.

Marc Iavaroni, 76ers starting power forward: Moses and Andrew Toney were constantly joking and ribbing and keeping people loose and honest in the locker room. I think it really helped with focus later on. Moses got on Andrew’s choice in clothes. Andrew would come in with a porkpie hat or something: “Hey, where you going? You going to the disco?”

Allen Lumpkin, 76ers ball boy: Moses was hilarious. Moses had such a sense of humor, and it affected everybody on that team. His laugh could clear a room. It was so hard and so loud.

Moncrief: That team was one of the best teams that I’ve seen in the history of basketball. As far as skill set and talent, they all fit. They didn’t trip over each other with their roles and responsibilities.

Gordie Jones, sportswriter, Lancaster Intelligencer Journal: Every game was kind of the same.

Iavaroni: Teams felt us coming, and in the fourth quarter, they folded. There were times where I’d come out, we’re down seven; Bobby would come in, and we’d win by five. That defensive five put teams in a stranglehold. We had great runners: We had Bobby on one wing, Julius on the other wing, and Maurice dishing. Teams got left behind by that type of defensive talent that led to buckets.

Nash: I would sit there in the press box thinking, “Golly, how lucky are we to be in this position?” You knew it was special.

The legend is, Moses Malone predicted a 76ers playoffs sweep with his forever-quoted “Fo, fo, fo.” Marc Iavaroni believes Malone meant that four wins were required in each series. Semantics aside, the team lost once before beating a depleted Lakers squad in four games to win the championship. There was some concern over Malone’s knees, but that ended quickly.

Katz: Moses’s heart was so big, he could play through injury. He played through injuries the whole year. I thought, “He’s just going to go through it.” And by the way, he just destroyed every center he played against all series.

Bill Cartwright, center, New York Knicks: I remember the [second-round] series. I was guarding him. I was all over him. I was grabbing him, holding him, no call, and he was still scoring. It’s like, wow. Wow.

Don Sperling, senior producer, NBA Entertainment: Moses was literally the only guy in the league that Kareem really had no answer for. He was too physical and too rough. Kareem would get in his rhythm with bounce-bounce and the sky hook. Moses never let him set up.

Cunningham: We had just won Game 3 (of the finals) in L.A. An hour later, I was in my room watching films, and Harold Katz came in and said, “Come on, let’s have some fun.”

I said, “You’ve got to be kidding me. I’ve come this close, and something could go wrong. There’s no way in the world I’m leaving.”

The next day, we go to shoot-around. The trainer, Al Domenico, says, “We’ve got a problem.” Moses must have gotten an elbow in the back and was having a difficult time breathing. He was going to take Moses to the doctor. I go over, and I say, “How you feeling, big guy?” He said, “Don’t worry. Kareem doesn’t want to see any more of me.” It kind of put me at ease a little bit.

Mark Piazza, 76ers director of media relations: I was sitting behind the bench in Game 4. Maybe halfway through the fourth quarter, I couldn’t do it anymore, and I watched the rest on the TV in the locker room. I remember being in the room with [equipment manager] Jeff Millman. It was a very nervous time; the game was very close. The one thing that sticks out in my mind more than anything was, as great a player as Julius was, clearly one of the greatest to ever play, it seemed like if he took a 10-foot jump shot — he made way more than he missed — you were always a little nervous when the ball was in the air. There was maybe less than two minutes to go. We were up two or three, very tense. He pulled up for a foul-line jumper, and Jeff and I were hanging on each other, yelling “NOOOO!” — and he nailed it. When he hit that shot, that’s when I knew we were going to win.

Guard Andrew Toney brings the ball up court during a game against the Milwaukee Bucks. / Photograph via Focus on Sport/Getty Images

Summers Gabriel: These guys were bawling their eyes out. Just the elation. Imagine that big fat smile on Andrew Toney’s face. Just to see the guys come out of it and be this family. As an office, we were so small that they were our boys. They were our team.

Steve McKenna, 76ers assistant ticket manager: When we were up on the floats, the people didn’t recognize who we were, but we worked as hard as anyone else. We were so proud of what we had done and been able to win. We felt like we had earned it as well. We all got the NBA championship rings. The players gave all the front office one of the shares for making the NBA Finals. It always felt like we were part of the team. We were part of the team.

Part V: “Imagine Michael Jordan running across the highway.”

The victory belonged to everyone. Today’s NBA teams are worth billions of dollars and have hundreds of employees. In the 1980s, teams flew commercial. “I’ve seen Julius Erving take his bag off the carousel a million times,” Mark Whicker says. Staffs were minuscule. The ’82-’83 Sixers had about 25 employees. Social boundaries were few. It wasn’t unusual to see Andrew Toney cracking jokes in the office or assistant coach Jack McMahon explaining strategy. “It felt like someone was there all the time, player-wise,” Dorothy Summers Gabriel recalls.

Per diem was $7. The hours were long. Few cared.

Summers Gabriel: It wasn’t the greatest job, but it was the greatest experience.

Toni Amendolia, 76ers group sales: We used to literally hand-count tickets. We’d have to manually record in our word processor what number tickets we gave to who, and Ron [Dick] and I would set out with directions to go deliver some of these group-sales tickets throughout the city.

Dick: That’s how I learned to drive in the city. I would get lost a lot. I didn’t understand how the one-way streets would go. I love Philadelphia, but it’s very unforgiving. Like, you’re going to get a horn in your butt, and they’re going to talk about your mom. They’re going to let you have it.

Malloy: We would go to New York and Jersey, because they were bus rides. The guys that lived in New Jersey — me, coaches Matty Guokas and Jack McMahon, players Clint Richardson and Bobby Jones — that’s a bus ride up the New Jersey Turnpike. The bus would leave the Spectrum parking lot. That’d take all the Philadelphia guys. Because we were going to be coming home at 1 a.m., we’d drive our cars out and park on the northbound side of Route 73, because we’d get right on Exit 4 of the Turnpike in Mount Laurel. We’d run across the highway and try not to get hit, like Frogger. The bus would pull into Bob Evans. We’d stay in the parking lot. The bus pulls in, the Jersey guys would get on. Imagine Michael Jordan running across the highway. It was insane.

Summers Gabriel: I had to climb on top of the Spectrum and meet up with the electricians. They were all like, “Oh, this girl, what is she doing?” I’d go up with 15 cassettes, and at time-outs, I’d have to play the music. If you didn’t have it queued up, oh my gosh, you lost the moment. If there was a time-out and there was no music, the phone would ring. There was a little bit of pressure. I think I got $35 a game. That was my car payment.

Swope: One time, I’m heading out to L.A., and Gabe [John Gabriel] said, “Would you mind stopping at Pepperdine to see this one kid play?” He knew that I knew basketball well enough to give him a feel.

John Gabriel, group sales, video scout, various roles: John Nash said, “You’re going to write and produce all our TV commercials.” I said, “Listen, I’ve never really done this before.” “We saw some of your portfolio from Kutztown. You can do it.” “When should my first commercial be ready?” “Yesterday.”

McKenna: There were a lot of characters.

Julius Erving rises above the Los Angeles Lakers during the 1983 NBA finals. / Photograph by Manny Millan/Sports Illustrated/Getty Images

Daniel Durso, 76ers director of finance: We had a trainer, Al Domenico —

Funk: He was a throwback to the old-time trainers. He had his little black satchel that he carried. Nobody really knew what he had in there.

Malloy: We used to kid that the only things in it were Band-Aids, ethyl chloride, and the latest racing form from Philadelphia Park.

Rabena: Everything he sprayed. It was like the movie My Big Fat Greek Wedding — everything was with the Windex. Well, this was everything with the spray.

Dick: I don’t even know if he passed all the training courses.

Amendolia: Harold’s line for Al when someone would come to him and say that Al did something that was not good business was, “Work around him.”

Funk: Al was one of the great all-time characters. He had a way about him that kept everybody loose, let’s put it that way.

Durso: “The reason we lost in Portland, because the sun was shining.” His other thing was, the team that scores the first point wins the game. He’d say things that absolutely made no sense, but everyone would go, “Actually, it sometimes works.”

We called them “Al-isms.”

Funk: “All great white jump shooters are left-handed.”

Malloy: “Let me tell you something, smoking is actually good for you.” I said, “Excuse me?” “Listen to me, smart-ass. What does smoking make you do?” I said, “It makes you cough and hack.” “Exactly. What is coughing? That is exercise for your lungs. You sit there breathing all day. You’re soft and flabby. I’m a robust cougher.”

Amendolia: Neil Funk would come in and torture John Nash and undermine his authority with the staff. He had a game that he would play — liar’s poker. And he would set up shop in the back of the office space. Everyone would come around with dollar bills. John Nash would come in all flustered and say, “Everybody back to work.” Neil would turn to him and say, “Listen, Pluto, if we wanted to know what you thought, we’d ask you.” And they were good friends.

Durso: When you work like that with everybody and they’re dependent on you and you’re dependent on them for help, you become a family. It’s impossible not to.

Malone, Cunningham and Erving celebrate the 76er’ Finals sweep to win the 1983 championship. / Photograph via Bettmann/Getty Images

Part VI: “Time and distance is nothing.”

The attitude shift Pat Williams saw in training camp in 1982 never returned. “We thought it would be there forever,” he says 40 years later.

The reasons given for the Sixers’ abbreviated dominance vary from person to person. Better teams. Age. Overconfidence. A lack of hunger in ’84. Ill-advised moves. What’s clear is, the team represented the final moments before the NBA’s transition to a sports entertainment industry began. Jack Swope isn’t bringing the championship trophy home in his Honda Accord for safekeeping; staffers aren’t battling Harvey “Super Stat” Pollack’s plumes of cigar smoke.

The following spring brought the first of three Lakers-Celtics finals, extending the narrative allure of Larry Bird vs. Magic Johnson that started in the widely watched 1979 NCAA basketball championship. In February 1984, David Stern became NBA commissioner and began constructing his version of Disney. Michael Jordan made his NBA debut on October 26, 1984.

Winning became a business, how franchises built their brands, says Lakers co-owner Jeanie Buss, who has had a front-row seat to the NBA’s decades-long evolution. The 1980s Sixers played a role. Their success, along with that of the Boston Celtics, attracted the New York papers, which improved coverage and piqued TV producers’ attention, says Terry Lyons, the NBA’s longtime PR guru. The NBA on CBS’s narrative- and personality-driven coverage was aided by Erving and Malone.

“People are attracted to stars,” says Ted Shaker, the NBA on CBS’s executive producer. “There’s a hell of a statement.” But it’s apt. In today’s NBA, little room exists for the past, unless it’s as debate (“Ain’t no way people believe Dr. J over MJ, right?”) or when a legend like Moses Malone dies.

A nostalgic diversion for many is the emotional crux of another person’s life, something a photo fails to capture.

The 76ers 1983 championship parade cuts though a crowd of 1.7 million on its way to Broad Street. / Photograph by George Tiedemann/Sports Illustrated/Getty Images

Iavaroni: To be in that group, I caught some flak. Anybody could have filled my role. I have no problem with that. They didn’t like the way I played. I have no problem with that. It’s just that everybody was so together on the common goal. When you see that being realized, it gives you not only great professional satisfaction, but personal satisfaction. No matter what they say about me averaging five points and five rebounds and 20-something minutes, I can always say, “Well, I got to drive them to games. I got to shower with them. I got to go to 9 a.m. practices.” To be around all that, that fuels you for a long time.

Williams: It is really, really hard to win a championship in any sport. But once you do, you’re never forgotten by the hometown city. All of the people who reminisce now, they were teenagers. Now they’re pushing 60, but it was a big part of their life growing up. That’s a precious memory that they still have and will always have. It’s the power of professional sports. It’s the impact of a pro team — and they don’t have to win it all. My most vivid memories growing up are of the 1950 Phillies; I was 10. I went to Game 2 of the 1950 World Series. I can still see it my mind’s eye. And Connie Mack’s A’s. How I loved those Eagles of Chuck Bednarik and Steve Van Buren.

It stays part of your life. It doesn’t leave you. That Sixers team — 40 more years from now, they’ll still be remembered.

Cureton: On a holiday, we all text each other. It wouldn’t take but 10 minutes to bring our team together 40 years later.

Reggie Johnson, 76ers forward: I still feel like we’re a family. We still reach out to each other. I hope that never dies. That’s something you can cherish for life.

Edwards: I look at those guys as brothers, man, always have.

Malloy: Time and distance is nothing. In August of ’21, my wife passed away of a brain tumor. Dorothy and Evelyn Canada and Toni Amendolia and Ron Dick and [director of group sales] Clayton Sheldon came to the funeral. From Florida, from Pittsburgh. They hadn’t seen Patti in 37 years. They hadn’t seen me in 20 years. Toni helped us run a fund-raiser that made $25,000 for Penn Medicine Brain Tumor Research Center. I hadn’t seen her in nearly 40 years. John Gabriel donated a painting that he did of Shaq’s shoes that sold for $1,500. That family, they bring me to tears with their generous spirit. We were all just good people, good to each other. I cry when I’m with them. It’s emotional for me to be with them today. Basketball is just a backdrop.

*Erving’s quote is from a previous interview with the reporter.

All titles and positions listed are from the 1982-’83 season. Quotes have been edited for clarity and space.

Published as “When the Sixers Finally Won It All!” in the May 2023 issue of Philadelphia magazine.